- Home

- Maria Gripe

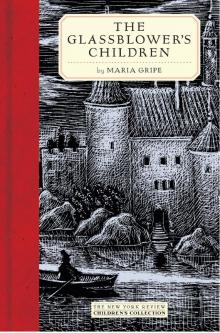

The Glassblower's Children Page 5

The Glassblower's Children Read online

Page 5

One of the reasons the servants were changed so often was that they broke so much glass. Recently, they’d been particularly slovenly and slipshod. Broken glass lay everywhere. New glass would be supplied immediately, but it would shatter just the same. And it proved to be impossible to find out who was to blame, for everyone denied everything, and they all protected each other.

A suspicious, unfriendly feeling grew in the House. Everyone spied on everyone else, but still no one managed to catch the guilty one. Everyone was baffled by how it could be done. Could someone be breaking the glass on purpose?

The Lord and Lady didn’t bother themselves about it in the beginning. They bought new glass and said nothing about it. But when it got worse and worse and when the servants suspected one another, so that the House resounded with their quarrels, then something had to be done.

The Lord ordered his old and faithful servant, the coachman, to find out who was breaking the glass.

This coachman was ancient and deadly solemn. He was stony-faced, and never let on what he was thinking. His silent and swift way of moving around was terrifying, for he walked as if his boots never touched the floor, but skimmed along just above it. His steps were stiff and jerky. He walked through the rooms like a wound-up mechanical doll or a puppet led along by its strings. This gave him a very inhuman look.

The coachman kept his plans and ideas to himself. He was sure he knew how to catch the guilty one.

First he got a large supply of glasses. These he planted in different places around the House so that he’d be able to tell right off which were breaking first and fastest. Then he would know what part of the House the criminal lived in.

The next step was to put more glass out again all over that part of the House and wait. Then he would creep around there like a dark spider circling its web. Doors opened and closed soundlessly, as if by themselves, when the coachman’s grey, stiff face peered in and disappeared just as swiftly, and then popped up right afterward in the door to another room.

Staring after him, the servants shook their heads.

“He’s getting old,” they said to each other.

And it was true, he was ancient, but not feeble. There weren’t many young people who could speed by as swiftly as he. It was weird; he seemed to be everywhere at once.

So it was all the more puzzling that he didn’t manage to trap the guilty one. Everything went on just the same. Glasses always crashed in places where he happened not to be. And several times he heard something break into a thousand pieces right in the next room, but when he opened the door there wasn’t a trace or a clue. The room would always be empty, but he’d find a glass completely shattered on the floor.

And he never heard a footstep. It had to be someone who could walk as silently as he did. And someone who was just as sly and crafty, too.

It was baffling. It both frustrated him and egged him on to try even harder. Occasionally the Lord came to ask how it was going, if he had found any clues. But he said nothing; he was masterful at keeping quiet. And it didn’t bother him that he had nothing to report.

Finally he thought up something really brilliant.

He had been wrong to put the glasses out in different rooms. This gave his enemy too many possibilities.

Of course he should have set them all out in the same place. And never just one glass, but a great many.

And so he arranged a big table, as if for a party, full of glasses and crystal carafes. He placed high-branched candlesticks around the table and lit them so that the glasses glittered and sparkled really temptingly.

Then he left the room. He closed the door very carefully behind him so that no one could guess his plot. But he didn’t walk away. He crept into a big empty closet in the next room. Slowly he pulled the door closed, leaving just a little crack open through which he could see who passed by. But he listened as hard as he could, too, because there was another door to the room where the glasses were and the guilty person just might use that one. And so there he stayed and waited and waited. But no one came. Not a sound was heard from the next room.

At last he grew very uncomfortable in the closet. He crept out and walked over to the door. He was very depressed. He opened the door soundlessly. Just then he heard a crash!

He stood still in the doorway. His face, as usual, expressed nothing, but his arms trembled impatiently, ready to grab their prize. He didn’t believe his eyes. He held himself back for a moment because he didn’t want to forget the smallest detail of the strange performance he saw before him.

The light in the room was soft and dim, for it was winter and late in the day. Crouching shadows hovered in the corners. But on the table the high candles glowed cheerfully and lit up the only person there.

It was Klas.

He stood on one of the chairs at the table, holding a goblet in his hand. The glass glittered, and he stared into it with a weird expression on his face. He was at once sorrowful, defiant, and triumphant. Suddenly, with all his might, he smashed the glass down on the floor, he stepped over to the next chair and grabbed another glass.

Thus he circled the room until all the glasses lay in pieces on the floor. Then he crawled down to run away. He was barefoot. He ran silently and very fast.

But there stood the coachman, blocking his way.

He stood like a shadow among the other shadows in the room.

All he had to do was put out his arm to catch Klas. It all happened in silence, for the coachman was a master at keeping silent, and Klas was speechless.

There followed a great commotion. Who could believe it! The servants, who had been wrongly suspected, were outraged. Loudly, in offended tones of voice, they announced they would work no longer. The Lady came down with a headache and told the Lord once again that the children were his find and that he had to look after them himself.

The Lord said he was astonished. He repeated this several times. The children were so dutiful and well-behaved.

Naturally, Klas had to be punished, he said, and pondered the problem a long time. Then he talked to the coachman, who went off to get a stout stick.

It hurt the Lord, but Klas had to be whipped for what he had done so that he would never do it again. The Lord explained all this and then he let the coachman give Klas a whipping. But he wasn’t to hit him very hard. . . .

Klas did it again. And then the coachman was ordered to hit him harder. And harder. And harder. But Klas still did it. Klara was ordered to spy on her brother. It didn’t help. Klas could outwit anyone. He showed astonishing guile. He was as clever as a fox and as quick as a weasel.

What could have come over him? There must be something wrong. He couldn’t bear to look at glass. And this even though his father had been a glass-blower! It was all very baffling!

But perhaps the children had been by themselves too much? Could that be the trouble? The Lord decided to find them a governess.

And that was how Nana came into their lives.

10

THE FIRST TIME Klas and Klara saw Nana she was eating.

The Lady led them up to where Nana sat, spread out along a bench on one side of a table. It was evening, but no lamps had been lit, so the room lay in dimness.

Nana had stuffed one corner of a light-colored napkin into her neckband. At first all the children could see was the glow of her napkin.

Then they lifted their eyes and looked right into an enormous open mouth, where a white lump of pastry was being churned and mashed around. They stared bewitched until the mush was swallowed, the mouth closed and then shifted into a bright smile.

Nana said good evening to them, and then the Lady left them in her care.

At that moment the servants carried in another course. Nana gobbled it and the children in the same glance—a glance that said: to my taste or not?

The dish came up to her expectations, but she was doubtful about the children. Her small, dangerous eyes studied them and knew at once that they were unhappy.

It didn’t matte

r what her opinion of them was—whether she liked them or not—she would devour them in any case. She was that sort.

There are no words to really describe Nana’s size properly. In both body and spirit she was an enormous person.

The Lord had decided that a fat governess must surely be the best kind, and that’s exactly why he had chosen Nana.

He told her that he didn’t want any more trouble from the children. And indeed he didn’t. He didn’t need to think about them any more. He didn’t even need to see them any more if he didn’t want to, for they would live as if chained to Nana’s body. She didn’t let them out of her sight for an instant.

From then on Klas and Klara had no life of their own. They lived Nana’s life. Just like the little, silent cockatoo, Nana’s house pet.

This was a terrified little bird that hunched in its cage and listened very carefully to everything Nana said. It nodded anxiously whenever she turned to it to show that it was following what she said and agreed with her. It blinked its terrified little eyes fitfully; it twitched and twisted its poor little body.

No one knew whether the cockatoo had been born unable to speak or had lost its voice faced with the thundering torrent of Nana’s words. The only sound it could get out now was a shrill screech that seemed to pierce the very marrow of everyone’s bones. Fortunately, it didn’t screech too often, only sometimes, in its sleep. No one could ever become hardened to that kind of noise. It would make the blood freeze in a person’s veins. All the unhappiness in the world was pitched in that scream.

The cockatoo was called Mimi.

Klas and Klara were eager to get to know Mimi, but Nana wouldn’t let them, and they were never able to. Mimi kept her eyes fixed on Nana. She never looked at the children. It was as if she didn’t notice that they existed.

But soon it was the same with Klas and Klara, too.

They had to keep their eyes on Nana, or else things could go very badly for them.

Every other hour Nana had to have something to eat. Then a big table was arranged for her, and she sat down on one side, with the children opposite her. The table groaned under the plates and platters loaded with food. Nana never had any trouble thinking up tasty treats for herself. But the children only ate when they were ordered too, dutifully. Otherwise they sat staring down at the silver dinnerware or into Nana’s enormous wide-open jaws.

Mimi perched in her cage next to Nana, who fed her the whole time with fig seeds that she kept in a bag. Mimi ate and swallowed them, dutifully and daintily, with the same seriousness a little schoolgirl shows, picking up knowledge from her teacher’s hand. You could stuff any amount of seeds into her. It was miraculous, because Mimi wasn’t a very big bird.

After she had eaten, Nana would yawn drowsily. She had to sleep to digest her food. Mimi seemed to pick up some strange kind of sleeping potion in Nana’s glance, for she began to yawn immediately.

A big canopied bed had been brought into the children’s room, and there Nana rested. As soon as she lay down, she fell asleep. It was as if a hurricane had swept through the room: first a murmur; then the roaring mounted, until at last she thundered. The curtains flapped like sails with her breathing, and the whole bed rocked like a ship in a stormy sea.

Mimi’s cage, which hung from a hook under the canopy, swayed crazily, but Mimi would hide her head under a wing and sleep through it all as if nothing were out of the ordinary. And she never woke before Nana.

Klas and Klara had to lie down as well, of course, but they could never sleep. They lay there, scared out of their wits, abandoned, until the bad storm died down and Nana woke once more.

She never slept longer than fifteen minutes. Mimi awoke promptly at the same time.

On waking, Nana would be terribly sharp and dangerous.

This was when she would take charge of the children’s education.

She owned a big trunk, in which she would root about and take out piles of books, abacuses, and slates to write on. Then she would begin her classes.

She tested Klas and Klara out of the books.

She hopped from one subject to another, from one book to another. And every time she closed a book, she slammed it so hard that the children shot up in the air. This she repeated again and again.

And they stood there like two foolish little idiots. They didn’t know anything. They didn’t learn anything. They understood nothing.

When it was obvious to her how dumb they were, she would plan their education. She ran crazily around the room, her arms flapping about so that her little eyeglasses, far down on her enormous nose, bobbed and jumped wildly.

Streams of warnings and bullying and scolding flooded out of her mouth. Then she would stop suddenly right in the middle of the room and shout, “REPEAT WHAT I HAVE SAID!”

A disagreeable silence would follow. Klas and Klara were unable to say a word. Pressed back against the wall so that she wouldn’t crush them, they stood there wild with terror. They looked as if they had been turned to stone. All their thoughts stood still.

Since they weren’t able to answer her, Nana would come over and pinch them.

She had remarkably small, nimble hands and feet. In fact, her feet must have been very strong indeed to hold her up. And there was strength in her fingers, too. That Klas and Klara could vouch for.

Every time Nana beat them, she said she had never worked with such badly brought up children. They were impossible to educate—she couldn’t make anything of them, she said, wheezing and puffing like a bellows. Yes, they were hopeless!

But then, even worse, the very worst, were her singing lessons. It was then they wished they were mute like Mimi. Nana was very demanding about singing.

She would have been a singer, she told them, if only people didn’t have something wrong with their hearing. And now she wanted to know if Klas and Klara had something wrong with their ears, too. So she would place herself right in the middle of the room and command them to listen carefully. She sang first, and then it was her idea that they should sing after her.

But she sang so high, so very high. And fright paralyzed Klas’ and Klara’s throats. They could only manage to squeak out tiny, hoarse peeps.

So Nana discovered that they, too, had something wrong with their ears. And ears like that had to be pinched. Never in all her life had she come across such unmusical ears, she said, and then she pinched them.

And this is how it went, day after day.

Klas and Klara sat at the table watching Nana eat. They lay in their beds listening to Nana sleep. They stood pressed against the wall facing the attack of Nana’s teaching.

To be in Nana’s care was to be in her clutches.

11

THE LORD AND Lady were completely satisfied with their governess. It was wonderful, too, how she was teaching the children, though it wasn’t necessary. Her frequent singing lessons were perhaps a little disturbing because Nana sang such high notes, but she told them that the children were very unmusical and had to practice often, so it really wasn’t her fault.

And there’d been no broken glasses at all since Nana came to the House. No one could deny that she was wonderful.

There was only one problem. You could overlook the fact that she had to eat every other hour, but her naps after eating were undeniably awkward. Not because she slept, but because her sleep was so noisy; she disturbed the whole House.

Every other hour, for fifteen minutes, all work stopped throughout the House. Everyone looked at everyone else in dismay: Nana is sleeping again.

It was more or less like a thunderstorm. There was nothing anyone could do about it; the storm had to have its own way. No one was exactly scared, just shaken, riled, unable to get hold of himself until it had passed.

That’s what it felt like when Nana slept.

The Lady suffered more than anyone else, for her bedroom was directly under the children’s. The storms raged right over her head. She didn’t feel that she ought to move just because of Nana. But finally, it w

as just too much.

She decided to move Nana instead. The children could be moved to another part of the House. But Nana would hear none of it. She said no, curtly. This room suited her. Here she kept her trunk full of school books, and here was her suitcase with all her costumes, which she always brought along in case she became an opera singer—and that’s what she would have become if only people’s hearing were a little better, she said, staring at the Lady’s ears so accusingly that the Lady drew herself back. She had no desire to discuss ears with Nana.

Another time, when the Lord quietly tried to point out to Nana that both her suitcase and her trunk could be moved along with her, if necessary, he was pierced by such a fierce stare that he trembled.

“I WILL NOT be moved about!” thundered Nana, and there the subject was dropped. They would just have to find another solution.

One day the Lord came home with a huge bottle of pills to cure snoring. Since the pills were supposed to quiet noises, he thought they might even help Nana. All he had to do was persuade her to take them. But she was easily riled, so he had to be careful not to upset her.

When she came in one morning complaining of exhaustion, the Lord hurried out and fetched the pill bottle. He told her the pills would give her a lot more energy, and that she should take one with every meal.

Nana took the pills and everyone waited excitedly.

But the only result was that she slept for half an hour instead of fifteen minutes. The terrible noises went on just the same.

Afterward she came and thanked the Lord and promised to go on taking the pills because she felt so much more energetic.

And so from then on the House was paralyzed for twice as long. It was a catastrophe.

The Lady had to take tablets to calm her nerves, and she wore ear plugs, too. She grew pale and looked rather frazzled. And there was nothing anyone could do about it, because everyone thought Nana’s work was so important. Everything else in the House depended on her, or that’s what people said, but in fact no one dared go against Nana. Everyone realized that Nana intended to stay there just as long as she pleased. Since her arrival, she was the one who gave the orders. And that was the whole truth.

The Glassblower's Children

The Glassblower's Children