- Home

- Maria Gripe

The Glassblower's Children Page 3

The Glassblower's Children Read online

Page 3

And then they met two girls who explained how they could make a good deal of money that day from passersby homeward bound from the fair. All you had to do was walk into the forest and pick wild flowers, and then stand down near the big road where the carriages and wagons passed. You just waved the flowers and then people would stop and buy them, because everyone had a lot of money that day.

What a good idea! Father and mother always had so little money. Where could they find flowers?

The girls knew that, too. They could show them. The forest was full of flowers. All kinds bloomed in there.

White and blue anemones?

Yes, lots of them.

And so the girls led the way. Klas and Klara followed them. It was just as they said. The forest fairly glowed with blue and white anemones, everywhere. They picked big bunches, all together.

They didn’t need to wander very far into the forest. There was no danger of getting lost, as mother and father were always so afraid might happen. The girls knew their way perfectly.

Later they took a shortcut through the forest down to the big road. And there was a sight to behold! Many children already lined the route, all waving bouquets at the travelers as they passed.

The happy farmers homeward bound were free and generous with their earnings. They often bought several bouquets, but perhaps Klas and Klara were too little or perhaps they didn’t wave their flowers as prettily as the others did, because no one bought from them.

Soon the girls had sold all their flowers, and ran off into the forest to gather some more.

Klas and Klara wandered a little further down the road to see if they couldn’t do better there. Klas’ arms grew tired and he dropped blossoms along the way. The little flowers began to droop and wilt, too.

But still they stood there waiting patiently. They weren’t particularly well dressed. In fact, they looked like little bundles of clothes out of which stuck tufts of hair. Their round mouths gaped and their blue eyes peeped out full of longing. They looked rather funny standing there, waiting for a miracle.

And the miracle came at last.

A fine carriage rumbled along, not one of the common kind farmers have with sturdy, stocky, slow horses, but a beautiful coach drawn by two sleek white horses, with a coachman on the driver’s seat. The horses galloped so fast that a white cloud of dust haloed each hoof and their manes streamed gloriously.

Now, this carriage had windows with curtains and, just as the carriage drove past Klas and Klara, someone inside waved.

A little further on the coachman reined in the horses and the coach came to a stop right in the middle of the road. The coachman got down and opened the door.

A crowd of children rushed over and collected around the coach right away, but the coachman drove them off. He beckoned instead to Klas and Klara. Can you imagine, he wanted their flowers!

Inside the coach sat a fine couple, a beautiful lady and a noble gentleman. They smiled at the solemn little children who stood there staring open-mouthed. The man, especially, smiled at the two of them. He said he recognized them; he had bought crystal from their father at the Blekeryd fair last autumn. Did they remember?

No, they didn’t. But he wanted their flowers, anyway. He said something to the coachman, who took out a big coin and gave it to Klara, and then the rich man told him to give one to Klas, too.

They were so astonished that they forgot to hand over their flowers, and the coachman had to tell them to give them to the fine lady.

The lady took them and laid them beside her on the seat. She scarcely glanced at them, but the nobleman said they were beautiful. And then he smiled again at Klas and Klara and asked the lady if she didn’t agree that the children were sweet.

“Yes,” she answered, “very pretty. Shall we drive on now?”

“As you wish, my dear,” he said, and nodded to the children. The coachman closed the door. He was really old, and before he clambered back up onto the box, he looked sternly at the children and told them gruffly not to lose the coins but to go right home and give them to their father and mother.

“Because that is a lot of money,” he explained very seriously.

The coach started off; a pale, pretty hand waved sadly through the curtains; the nobleman’s face could be seen briefly; but then the horses pulled away so swiftly that the coach disappeared in a cloud of dust.

Klas and Klara stood speechless, gaping after it. Almost immediately all the children surrounded them to see the coins. And surely they would have lost them very soon if Sofia hadn’t come running over that same instant. She was white with fright.

Her feelings changed to astonishment when she saw what the children had been given. Astonishment and delight.

“Real gold coins!” she told them.

They walked home to wait for Albert, but now Sofia didn’t dare run down to the crossroad any more. She stayed very watchfully inside.

The day ended and night came. Still no Albert. He wasn’t home until after ten o’clock.

By then the children were fast asleep in the chest of drawers.

He had been delayed by an unexpected misfortune: The farmer had, of course, got quite drunk at the fair and had driven like a madman, so that on their way home the wagon had rolled straight into a ditch. Every single glass had been smashed, but that didn’t make much difference, since no one wanted his work anyway. He hadn’t been able to sell a single piece. As usual!

No rich folk had come to buy from him this time, either. Albert was depressed and fed up with everything.

Sofia looked as if she were bursting with secrets, but said nothing. Then, when he had finished telling her what had happened, she took out the gold coins that the children had received and showed them to him.

“Wealthy folk have been here, and that’s for sure,” she said.

Albert’s eyes opened very wide.

“But you had nothing to sell,” he exclaimed.

“I didn’t,” she laughed, “but the children did. They gathered flowers and sold them down by the road.”

Then she told about the fine coach with the noble couple who wanted to buy only from their children, not from the others. Sofia was so proud, but Albert frowned. He wasn’t as happy about the story as she. In the first place, he didn’t like the fact that she had left the children unattended.

And then it was bitter for him to realize that a handful of wilting flowers could be worth more than his glass. What was it all worth, his glassblowing?

And so ended the fair that spring.

6

A SUMMER CAME and went, and then a winter, too, and thus the spring of a new year returned.

Albert and Sofia watched the seasons change and their children grow bigger, but otherwise everything stayed much the same. Their life plodded along the same old ruts.

Whether it earned him money or not, Albert had to keep making his glass, for while he worked he was always happy. Nor did he worry whether the pieces would sell or not. When at work he forgot everything else and felt content.

How he longed to be able to stay in his workshop and avoid going to the fairs! But they were in fact his only way to sell, for in the village few people ever needed glass, and no one could make a living selling there.

But as for Sofia, she always looked forward to each and every fair. She lived for them. And this spring he’d promised that she could come along. The children were so much bigger now. And the fair at Blekeryd came later this year than usual, at the end of May, so that they could count on fine, warm weather.

At each fair Sofia always thought Albert would have great success. Someday it just had to work out for them, she thought. Some time it had to be their turn for good luck. Why not this next fair? Yes, at every fair she felt sure that now, NOW it was going to happen! Albert would sell all his glasses and every one of his bowls.

She boosted Albert’s confidence this way as they packed the wagon full of glass, until at last he, too, was all afire with hope. When they set off that beautif

ul May morning, they were full of joy and expectation.

It was also a marvelous day. The wild cherry trees were just at the peak of their bloom, spreading their scent afar, and the dandelion seeds sailed through the sunlight over the fairground. On such a day as this, surely all would go well.

It looked as if everyone thought the same. An uncommonly large crowd had gathered, and the fair offered more amusements than usual. One man had put up a Punch-and-Judy theatre. A real carousel had come, and in one tent a snake charmer and several sword-swallowers performed. One organ grinder had brought a bear with him, and another a monkey.

Many more children had been allowed to come along, too. The gypsies, of course, always had their lovely children with them, but other children showed up. The place was alive with them, echoing with joyful shouts.

When Sofia saw this she told Albert it was good that Klas and Klara could come, for they really needed a little entertainment. Of course Albert agreed.

There was so much for the children to see.

Especially wonderful was a shop with dolls. An old woman had made all the dolls herself. They sat and stood on shelves or hung from the roof beams by lengths of string. They were large, almost like little children, and had the most delightful blue button eyes and curly hair. The clothes were so realistic and well-made that everyone who saw them marveled.

There was always a crowd around that shop, both mothers and daughters, touching the clothes and stroking the dolls’ heads and sighing with delight. But not everyone could buy them because the dolls were expensive. Most people had to wait and see how their own sales went before they could think about buying a doll. Only rich people from the city could buy them right away.

Sofia and Klara had already been over to the doll shop several times to see which doll they liked the most. They picked out one of the largest, most expensive ones, and neither of them seriously believed that the doll would ever be theirs, but it didn’t cost anything to wish. Her blond hair was braided in long golden plaits; she wore a black satin cloak and a lilac kerchief. You couldn’t describe how pretty she was.

Every time Sofia took Klara with her to look at the doll, both of them worried just as much that she might already be sold and gone. But imagine, she still hung there in her corner, swinging from a little string. It was exactly as if she were waiting for them, they thought.

And then, when Albert actually sold a pair of goblets, Klara’s hopes became more real. And Sofia’s, too. Perhaps after all. . . .

Of course the other glassblower with whom Albert shared the shop sold the most as usual, but he didn’t have as much with him this time. And people felt in a fine mood because of the sunshine. They were eager to buy.

The other man had already sold out before the morning was over, and so people started coming to Albert instead. It went really well, and soon Sofia had to help him.

Because of this she couldn’t keep an eye on the children all the time, but she told them to stay nearby. And they did, too. They behaved very well in the beginning. But then Klara decided she had to go over and see the doll again.

She wandered off with Klas. Of course she knew the way, because she and her mother had walked it so often. But how much there was to look at everywhere! And what a crush of people running this way and that! Swept up in the rush, the children began to run hither and thither like everyone else.

And every now and then some gypsy children came up to them, and they would play together for a while. And then they’d set off again, and they walked . . . and walked . . . and walked. . . .

Suddenly Sofia noticed that the children didn’t answer when she called. She ran out of the shop. They were nowhere to be seen. She asked the shopkeepers nearby. They knew nothing. But what danger could there be, they said. The children would be all right. Why shouldn’t they look around a little?

On such a blessed day no one need be afraid!

No, that was the truth! Sofia wasn’t exactly frightened, either, but she told Albert that he would have to manage alone for a while because she had to look after the children. She didn’t want to tell him what had happened because that would have upset him needlessly. When she thought about it, Sofia realized that Klara must have wandered off toward the doll shop.

Sofia hurried over there. As usual it was crowded with people, but her children were not among them. She described them and asked if anyone had seen them. No, they hadn’t shown up, at least not recently.

In that case they must be on their way back, Sofia decided, and hurried off. But then she thought that as long as she was there, she’d see if the doll with the satin cloak was still for sale. They might be able to buy it after all, if they could keep on selling so well all day.

But the doll was gone.

And then her spirits fell very low indeed. Poor little Klara, such a disappointment for her. Sofia just had to ask if the doll was really sold or if perhaps it had been taken down from view. She pushed her way through the crowd up to the old woman.

Yes, indeed, the doll was really sold.

“Oh, alas, what a shame! I wonder who bought it?” Sofia asked, mostly to herself. But then what a strange answer she heard!

The old lady told her that a little girl had come and bought the doll. And in her opinion it was outrageous that little children should be allowed to buy such expensive things by themselves. The little girl wasn’t with an adult, only her little brother. It really was the limit, said the old lady, to send children out with so much money. . . .

Sofia, seized by a terrible foreboding, asked what the children looked like. From the description, there was no doubt about it: they were Klas and Klara. She was absolutely terrified. Where in heavens had they got the money?

She asked the lady in what direction they’d walked away, but she didn’t know. She’d only noticed how blissfully happy the little girl looked setting off with the big doll in her arms and her little brother trailing along after her.

How long ago could that have been? The old lady thought it must have been a good hour at least.

Her heart pounding with fear, Sofia ran back to the shop. Perhaps the children had already returned. Of course they must have lost their way for a while. It wouldn’t be easy for them to see their way through the crowd of tall, bustling people.

But there were no children back with Albert. He hadn’t seen them. He turned pale and panic-stricken when Sofia told him about what had happened. He dropped what he was doing and rushed off to search for them.

Now the fairground was really very large. They could have wandered far afield. And surely not everyone there was nice and kind, Albert said. You could never really know what strange people might come to a fairground.

Sofia tried to calm Albert.

It was truly such a wonderful day. Everyone would be nice and happy. No one could want to harm two small children, he must believe that!

Albert didn’t answer. His face tense with effort, he searched on and on, relentlessly. He asked everyone. They all gave him the same answer, that the place was crawling with children. How could you be sure which ones you’d seen? But they promised to keep a look out. There really wasn’t any danger. Think how playful children run off for a while and hide.

But the hours passed and the day sank slowly into dusk. Albert and Sofia had abandoned their glassware completely. And this was the one time they had been able to sell. Surely they had boasted . . . been over-proud. . . .

They searched, wandering like lost souls. And others helped them, too, now that they understood it was serious. For no children playing a game would hide so long. If nothing else, they would surely become hungry and thirsty.

Finally they had searched through all the wagons left in the woods around the edge of the fairground. Perhaps the children had lost their way there, become tired, crept inside one of the wagons, and fallen asleep.

But they weren’t there, either.

They had disappeared without a trace.

At the doll shop the trail just ended. After

ward not a single person had seen them.

The day had been warm, but now evening brought a refreshing coolness. The moon rose, big and pale and bright. And the shimmering blue air was filled with song and the sounds of games and laughter. But neither Albert nor Sofia saw or heard what was happening around them any longer.

Sofia was beside herself. She stumbled on by Albert’s side, and once an accident almost happened. She tripped and fell right in front of a big, elegant coach, slowly easing its way through the pleasure-seekers. It was a black, closed carriage, drawn by two horses. Curtains in the coach windows were elegantly drawn. Curious eyes watched the coach pass by.

People staring after it would have been astonished had they known that behind the curtains two lonely children slumbered in each other’s arms. A large fairground doll had slipped out of the girl’s lap and fallen to the floor of the coach.

And this was the coach that nearly ran over Sofia. The man on the driver’s seat reined in the horses instantly. They reared. Albert grabbed hold of Sofia and pulled her toward him. The coachman glanced blankly at the crying woman who hadn’t looked where she was going. Then, urging the horses on, he drove off, finally clear of the crowd in the fairground streets.

The last he saw was an eccentrically dressed old lady who suddenly appeared from the shadows mottling the moonlight and fluttered a little way ahead of the coach. She wore a cloak with a big floppy collar and looked just like an old bird.

When the coachman drove past her, she looked straight at him, so penetratingly that he became weirdly frightened. She held her ground and stared at the coach until it swung away around a bend in the road and disappeared from her sight. This was a relief to the coachman. He had felt her eyes staring at him the whole time.

They traveled all through the night. Northward. No one knew what roads they took.

The forests stood dark and silent, so that one could hear the wood nixie sing. She was dangerous, the wood nixie, especially for young men. But the coachman looked neither to the right nor the left, for he was old and didn’t let himself be enticed.

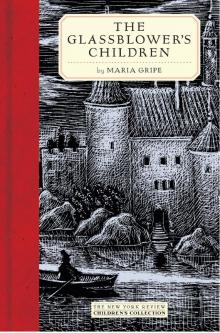

The Glassblower's Children

The Glassblower's Children